2040 Transportation Master Plan

Existing Conditions

Kelowna is the largest city in the B.C. Interior. Our geography, climate, economy, and lifestyle opportunities make it a desirable place to live. As one of the fastest growing cities in Canada, Kelowna is quickly transforming from a “big town” into a “small city”.

Like many places in North America, Kelowna built up around the automobile, and as a result driving remains the default way most residents get around. Roughly four out of five trips within the city are made in a personal vehicle. At the same time, Kelowna’s relatively small size, hospitable climate, and flat terrain in the central parts of the city mean that walking and biking are much more popular here than other parts of Canada.

A complete summary is available in our TMP Existing and Future Conditions Technical Report.

Kelowna is a geographically diverse city. Within its boundaries, Kelowna has everything from populated urban areas dotted with high rises, to agricultural areas filled with farms, orchards, and vineyards. The 2040 OCP includes five Growth Strategy Districts (see OCP Map 1.1), each with their own unique transportation options, challenges, and opportunities:

Kelowna’s five Urban Centres (Downtown, Pandosy, Capri Landmark, Midtown, and Rutland) are its economic hubs. They are the busiest areas of the city where competition for street space is highest. The concentration of activity in Urban Centres means there is not enough space for everyone to drive all the time.

People from all over the region make trips into the Urban Centres. Approximately 40 per cent of Kelowna’s jobs are in the Urban Centres but only about 15 per cent of its residents live in these areas. This imbalance contributes to traffic and parking challenges as large numbers of people try to enter and leave at the same time.

Trips within the Urban Centres tend to be short, which means walking and biking can be convenient ways for people to move around.

The Core Area generally refers to the flat parts of the city on the valley floor and neighbourhoods near the Urban Centres. Most homes in these areas are detached housing with some multifamily development and commercial land located along major corridors.

Many places in the Core Area have streets arranged in cul-de-sacs rather than a grid pattern. This makes it much longer to walk or bike if cul-de-sacs are not connected by pathways, and it concentrates traffic on a few major streets.

Most of the Core Area was designed around driving but has the potential to shift to other modes. The gentle terrain and shorter distances between destinations means walking and biking can be convenient. Public transit can be a competitive option, particularly along corridors between major destinations.

Suburban neighbourhoods are home to roughly a quarter of Kelowna’s population but only about five per cent of its jobs. This imbalance leads to a surge of commuters travelling to work or school in the morning and returning in the evening.

Steep hillsides often lead to branching street networks with many long cul-de-sacs. The roads connecting these neighbourhoods often resemble a network of streams joining to form a river. An entire neighbourhood may have a single point of access, which creates challenges for emergency response and evacuation.

Driving is often the only option for getting around hillside areas. They are typically too hilly and far away from destinations to make walking or biking feasible options. Their low density makes it very expensive to provide the level of transit service needed to compete with driving. Snow removal is also more expensive to provide.

The Gateway includes UBC Okanagan, Kelowna International Airport, and the surrounding industrial lands. It is expected that roughly one in five new jobs over the next twenty years will be located here. The number of students at UBC Okanagan is expected to significantly increase.

Transit ridership is high among people living on the UBC Okanagan campus and its adjacent neighbourhoods. The Kelowna International Airport also provides an opportunity to improve access by transit. Other industrial parts of the Gateway are difficult to reach using an option besides driving. Transit service that is frequent enough to compete with driving is challenging to provide in lower density industrial areas.

Many destinations are close to the Okanagan Rail Trail, which provides the potential for some trips to the Gateway area to be made by bicycle. Electric bikes may help facilitate longer trips to the area.

These areas consist primarily of agricultural lands, with some pockets of residential properties. Roughly four per cent of Kelowna’s residents and 12 per cent of its jobs are on rural lands.

The roads in these areas are often narrow, with tight corners and intersections at irregular angles. Sidewalks and bike lanes are rare. This is not an issue when roads are quiet, but challenges have emerged when rural roads get busier.

Personal vehicles are the primary way rural residents get around. Low densities in rural areas make them inefficient to serve with public transit. Distances are often too far to walk or bike, though some rural roads will have people walking and biking on them (often for recreation).

On a typical weekday, Kelowna residents travel about 2.6 million kilometres, or the equivalent of going to the moon and back three times.

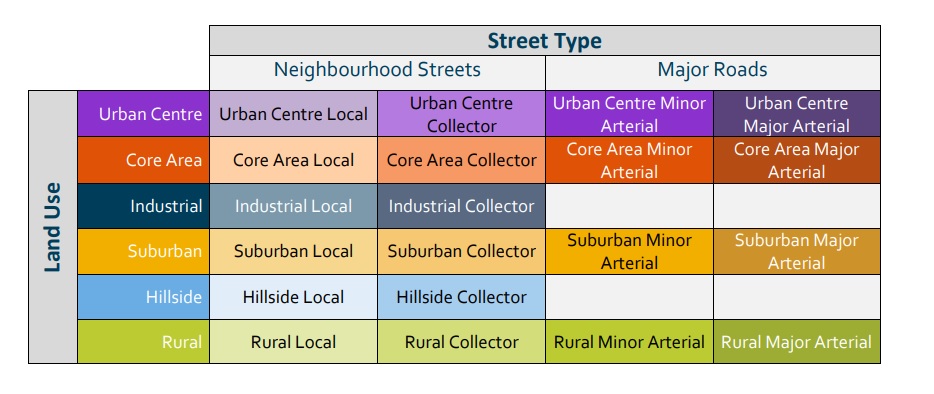

Travel demand is defined by peaks that follow the rhythm of daily life in Kelowna. The weekday morning peak is a sharp spike that is dominated by commuters going to work and school. The afternoon peak is more of a gradual wave, with different groups of people travelling for different reasons at overlapping times. There is a midday peak just before noon. Interestingly, even at the peak of rush hour, only one in seven residents are travelling at a time.

| Travel demand is defined by peaks Number of trips by hour, fall weekday (2018) | |

|

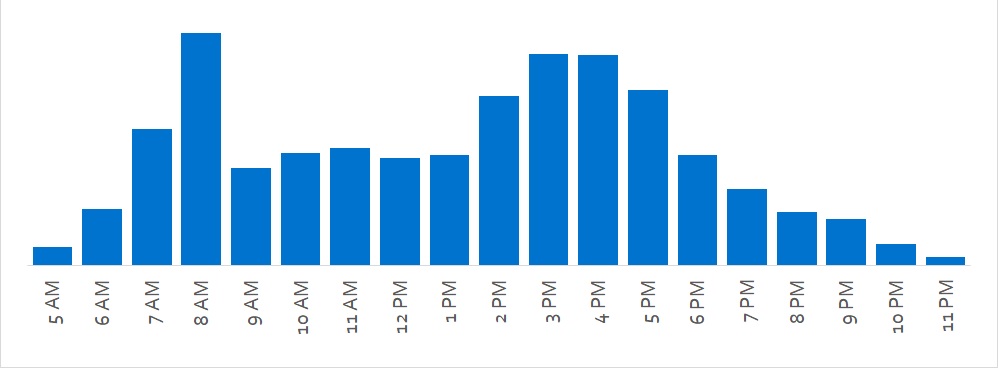

Travel behaviour varies by age. People under 25 make the fewest number of trips and travel mostly in the morning peak and early afternoon around school bell times. People between 25 and 60 travel the most, which is likely related to commuting to work and transporting children. Older adults tend to avoid peak hours, travel more in the midday, and make fewer trips than working adults.

Children under the age of 14 make two-thirds of their trips as vehicle passengers. Public transit is most popular among young adults 15- to 24-years-old. Driving peaks in middle age, then begins to decline for older adults who tend to work less and make fewer trips to pick up and drop off children.

| Older adults travel less during peak hours Share of residents travelling, by age group, fall weekday (2018) | |

|

The most common destinations during the weekday morning peak are workplaces and schools. Just over one-third of travellers are heading to destinations downtown, near the Kelowna General Hospital, or in the Capri-Landmark or Pandosy areas. About 10 per cent of travellers are heading towards the Gateway.

Commuting to work and school is the most common reason people travel during peak hours. The average commute times in Kelowna is about 18 minutes, which is comparable to other Canadian cities of a similar size.

Trips to and from work and school only represent one-third of travel throughout the day. During the midday, more trips are being made for shopping and services. The Midtown area, including Orchard Park, accounts for nearly one in five trips during this period. About two-thirds of residents are away from home at midday.

Destinations are more dispersed during the afternoon peak. Many people are returning home, while others are making recreational or shopping trips on the way.

The distance of people’s trips strongly influences how they choose to travel. Walking is most common for trips under a kilometre, or a 10- to 15-minute walk. Nearly all bike trips are shorter than five kilometres, or a 20-minute ride. Higher speeds (e.g., by car or transit) are needed to travel longer distances in a reasonable amount of time.

Driving is the most common way people in Kelowna get around. On average, four out of five trips are made by personal vehicle (either as a driver or a passenger).

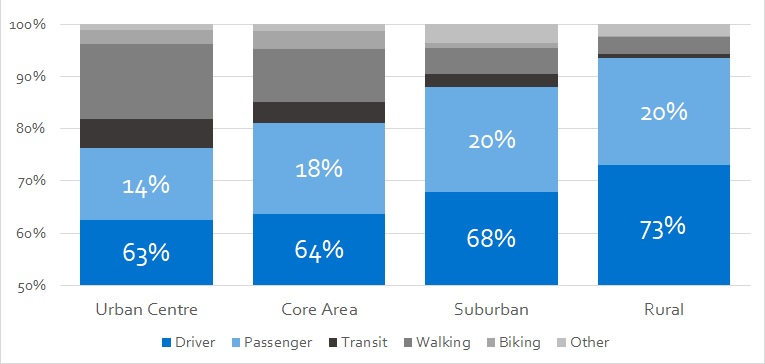

How people choose to get around varies substantially based on where they live. Since households in outlying and hillside areas must travel longer distances to meet their daily travel needs, over 90 per cent of these residents travel by car and drive two to six times farther compared to those living in Core Area neighbourhoods (as shown in Map 2.1). This contributes disproportionately more to traffic congestion and emissions. Conversely, trips by walking, biking and transit are much higher for households located in the Core Area, and when residents drive, they drive shorter distances.

| People living in Urban Centres drive less Share of trips by mode, fall weekday (2018) | |

|

People are more likely to walk, bike, or take transit for routine trips, like commuting to work or school. They become familiar with the requirements and time needed to make these repeat trips. It can be hard to make spontaneous trips by transit unless the next bus is coming soon. Shopping trips are more likely to require carrying cargo, which can make driving more convenient.

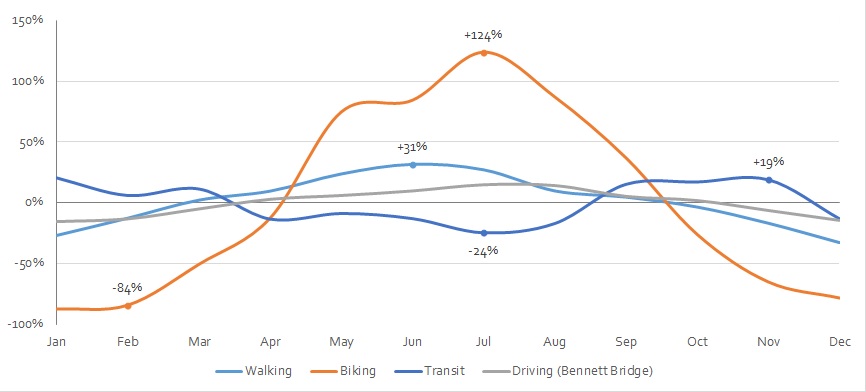

Travel patterns in Kelowna change with the seasons. Our population grows in the summer with visitors and part-time residents.

Car travel is relatively stable, varying by 25 to 30 per cent over the year and peaking in the summer. Daily traffic volumes on the WR Bennett Bridge are about 30 per cent higher in summer than in winter. Most of this extra volume is during the midday peak.

Transit ridership varies by 40 to 50 per cent over the year, peaking in the fall and falling over the summer (a trend influenced by the school calendar).

Compared to other means of travel, trips by bicycle fluctuate the most throughout the year (by over ten times between summer and winter). In winter, inclement weather, less daylight and limited snow clearing make bicycling less attractive. In summer, bicycling trips peak, making it a valuable relief valve when traffic pressure on the roads is highest.

| Biking is most popular in the summer Monthly activity by mode, as a share of annual average | |

|

More information on existing conditions is available in our TMP Existing and Future Conditions Technical Report.

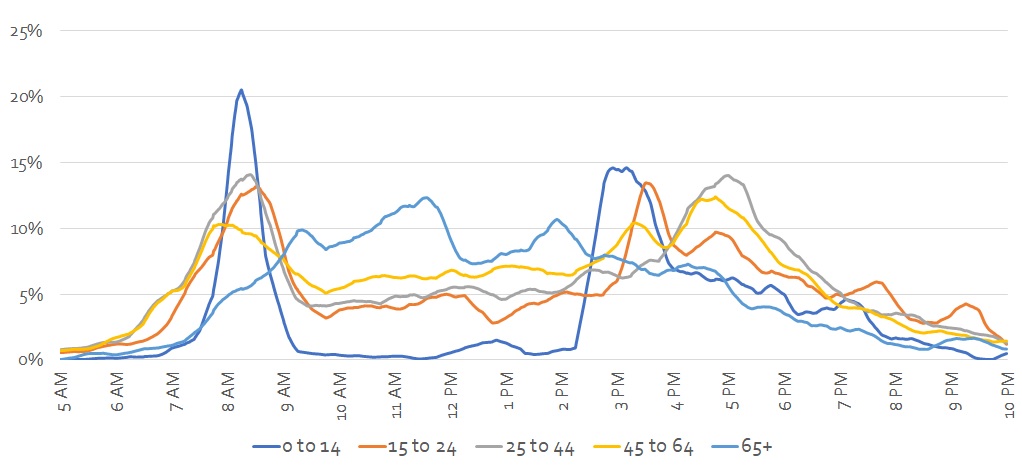

Kelowna has roughly 800 kilometres of streets, from major arterials to small residential streets. Some are designed to move people and goods across the city. Others are intended to support local businesses or provide attractive places to live. Defining the role of a street can help clarify expectations and inform design choices.

Kelowna’s street types and land use contexts are described below.

The role of a street is influenced by its location in the hierarchy of the street network. Some streets prioritize mobility (moving quickly) while others prioritize access to businesses and residences. For example, a highway moves people and goods over long distances by limiting crossings, driveways, and places for drivers to get on or off. On the other hand, a laneway provides direct access to homes or businesses, and services such as garbage collection, but does not allow people to move quickly. Most streets fall somewhere in between. We can divide streets into two groups along this continuum: the Major Road Network and Neighborhood Street Network.

Major Road Network:

The major road network includes the following road types:

• Highways are major arterial roads that connect the city to other places. Highway 97 provides connections across Okanagan Lake and north to Lake Country. Highway 33 provides connections east to Big White and beyond. While highways are under provincial jurisdiction, they support a large amount of mobility within Kelowna, influence our intersections, and are close to many important destinations and services.

• Major arterials are designed to move people and goods over longer distances across the city. Traffic speeds and volumes mean that people walking and biking need to be separated from vehicles to feel safe. Parking is rare on major arterials and driveways are discouraged. Many, but not all, major arterials have multiple travel lanes.

• Minor arterials are designed to move people and goods over medium to long distances connecting neighbourhoods. Parking is generally limited on minor arterials and driveways are discouraged. Minor arterials typically have two or three lanes. Traffic speeds and volumes often mean separate facilities for people walking and biking are preferred. All arterials are expected to carry a diverse mix of traffic, including large trucks, public transit and people walking and biking.

Neighbourhood Street Network:

The neighbourhood street network includes the following street types:

• Collectors are designed to facilitate travel over shorter distances. They connect local streets to arterial roads and provide access to homes and businesses. Some on-street parking and driveways are present, and vehicle speeds are lower than on the major road network. Sidewalks, pathways, or bike lanes for people walking and cycling are often provided.

• Local streets are primarily intended to provide direct access to homes and businesses. They are often quieter, and vehicles are expected to drive slower and mix with people walking and biking. On street parking and driveways are typical.

• Laneways provide access to residences and businesses, often in higher density areas. They typically consist of one shared travel lane, accommodating either one-way or two-way traffic depending on the context, with very low traffic volumes and speeds. Vehicles share the space with people walking and biking. Businesses often use laneways for loading and unloading goods. In residential areas, laneways are sometimes used for social activities.

The role and function of a street is also heavily influenced by how the surrounding land is used. Travel patterns, types of vehicles using the street, and levels of walking, bicycle, and transit activity, can vary substantially. For example, a major arterial in a rural area will be used differently and have different design requirements than a major arterial in an urban area.

• Urban Centre streets have the highest levels of activity happening in the same space (e.g., people walking or biking, transit, deliveries, parking, pick-ups/drop-offs, outdoor dining, public plazas). This means vehicle speeds need to be slower. Businesses benefit from wider sidewalks and parking. Trees add shade and make a street more walkable and attractive. Streets in Urban Centres are more complex, and greater care is required to design and manage them.

• Core Area streets may support residential or commercial land uses and typically have more pedestrian, biking, and transit activity than streets in suburban areas. Core Area streets accommodate both vehicle travel and people biking and walking, with an emphasis on separating people walking and biking from motor vehicle traffic, where feasible.

• Industrial areas share characteristics with suburban areas but typically have higher truck volumes, which need to be considered in their design and operation.

• Suburban streets typically support lower density, residential neighbourhoods. Motor vehicles dominate travel, with fewer people walking and biking. Suburban neighbourhood streets (locals and collectors) are meant to be attractive places to live, where people can stroll, walk their dogs and where children can play. Meanwhile, major roads in suburban areas need to safely accommodate vehicles moving at higher speeds with separate facilities for people walking and biking. Some Village Centres within suburban areas may have more people walking or biking, similar to streets in the core and urban areas.

• Hillside streets are similar to suburban streets, but the steep terrain requires adjusting the street design. Hillside streets are predominantly designed to serve motor vehicles, with fewer people walking and biking than suburban streets, due to the combination of few walkable destinations, longer distances and steeper grades.

• Rural areas are typically very low density and support agricultural land uses. Streets are used primarily by motor vehicles, including slower-moving agricultural vehicles like tractors. There is a lack of on-street parking and sidewalks, so any people walking or biking must use the shoulder.

The street types and land uses described above combine to form the City's Functional Classification System. These classifications help determine priorities for activities like snow clearing or street sweeping and the requirements for new developments.

Kelowna’s street network has evolved over decades and will continue to change. While the classification of some streets may seem out of place for today’s conditions, it accounts for future growth outlined in the 2040 Official Community Plan.

The Functional Classification Map (Map B.1) also includes key roads that do not yet exist, but are planned for the future. These may be roads recommended within the next 20 years, longer-term projects beyond the TMP’s 20-year timeframe, or roads connected to the development of specific properties.

Please note that the Functional Classification Map does not show laneways or emergency accesses.

The Functional Classification System is a part of both the 2040 OCP and 2040 TMP. Typical cross-sections associated with each functional class are part of the Subdivision, Development & Servicing Bylaw (Bylaw 7900). Updates to align Bylaw 7900 with the 2040 OCP and 2040 TMP are currently underway and will follow endorsement of the 2040 TMP. The Functional Classification System and Bylaw 7900 work together within a larger system of policies to guide the development of new transportation infrastructure.

The functional classification system describes many of Kelowna’s streets. Some streets have unique roles which are outlined in the following four overlay maps.

Transit Overlay Map

- Map B.2 shows current and planned transit routes where additional space may be required for bus stops. Since most people walk to and from a bus stop, it is important to ensure these streets have good sidewalks and convenient places to cross and catch the bus. Special attention is necessary to accommodate larger transit vehicles along these routes.

Bicycle Overlay Map

- Map B.3 shows streets where additional street right-of-way is typically needed to separate people biking from vehicle traffic. Primary bike routes are intended to accommodate people of all ages and abilities (e.g., Ethel, Sutherland, or Cawston). Secondary routes are usually bike lanes that connect people to the primary routes and their destinations.

- The Bicycle Overlay is based on the Pedestrian and Bicycle Master Plan (2016) and has been updated to reflect the project priorities in the 2040 Transportation Master Plan.

Truck Route Overlay Map

- Truck routes are important for the movement of goods and to support local businesses. While trucks and commercial vehicles use the majority of the road network, Map B.4 shows where more truck traffic can be expected. In rural areas, agricultural truck traffic can increase during certain seasons. Special attention is necessary to accommodate larger vehicles along these routes.

DCC Project Overlay Map

- Map B.5 shows places where new roads or retrofit projects are planned over the next 20 years as part of the Development Cost Charge (DCC) Program. This map also includes recommended projects that are not yet funded but that are likely to become DCC projects in future updates.